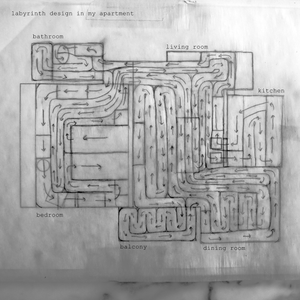

This piece was made during California’s “Stay at Home” orders, which were imposed in response to the outbreak of COVID-19. The work is about walking, embodiment, point of view, and landscape. The space in which I walk, a temporary living situation that has been prolonged due to COVID-19, is not my home. The furniture and objects in it do not belong to me, and yet, like others who are fortunate enough to be quarantining safely at home at this time, my experience of the physical world has been largely reduced to this domestic space. As a result, I have developed a peculiar intimacy with these rooms, as they have become my near total landscape. In them, I have used tape to create a single pathway that covers every scalable surface, including furniture, in a wall-to-wall labyrinth in which floor becomes ground, and couch, tables, and countertops become mountains to climb. The labyrinth is a means of taking a journey through a confined space, while simultaneously defamiliarizing an otherwise known environment. It is my way to engage with ground, path-making, infrastructure, and how the built environment determines experience.

The act of walking plays a significant role in the history of art. In this walking work, I have situated cameras on my body (on my feet), as opposed to having my walking body recorded by a third party or “objective” point of view. I am obsessed with the circular relationship between subject and object, and for this piece I attempted to collapse the relationship by having my feet serve as both simultaneously. In her 2002 article, “The Persistence of Vision,” Donna Haraway argues that what she terms a feminist, embodied objectivity must be grounded in situated knowledge. “Objectivity” she says, “turns out to be be about particular and specific embodiment, and definitely not about the false vision promising transcendence of all limits and responsibility. The moral is simple: only partial perspective promises objective vision.”

I chose the points of view from my feet because, as an embodied exploration of moving through a landscape, I wanted to bring a deep sense of attention to the body’s points of connection with the ground into which they intermingle and extend. In his 2010 article, “Footprints through the weather-world: walking, breathing, knowing,” anthropologist Tim Ingold argues that our bodies extend into the ground and air, and that the ground and air extend back into us. In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s description of the ground as vibrant soil reminds us that the ground is literally a living substance, as opposed to something inert and agentless. The walking performed in this piece takes place in a built structure, which was itself built into the ground below it. My feet interact with the manufactured products of the American building trade, including engineered wood, stone, textiles, and plastics. I am interested in how landscape determines experience, especially the landscape of built environments. Jedediah Purdy, in his 2015 book After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene, says, “[w]e are creatures of our built environment, an infrastructure species. By changing it, we change ourselves.”

Another method for transformation is the pilgrimage. Rebecca Solnit describes pilgrimage as a journey in physical space that maps onto an internal journey of transformation. In conducting my research for this project, I learned about the histories of the ground I walk on as an Angeleno. For instance, I learned that many major Los Angeles roads were built on ancient pathways cut into the land by the people who lived (and live) here before me or my ancestors arrived. In learning this, it has helped me more deeply learn that one’s positionality is never neutral. For that reason, this piece is very personally relevant. It signifies both an embodied and internal journey in which I attempt to get my own “feet on the ground” of the land, culture, and time in which I live.